Unix time values (the epoch)

Unix time (often called “the epoch”) is a simple way to represent a point in time: the number of seconds that have elapsed since 1970-01-01 00:00:00 UTC, not counting leap seconds. It’s compact, language-agnostic, and easy to compare and sort.

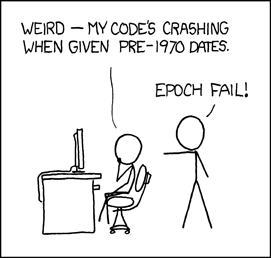

Comic: xkcd #376 — used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License. Credit: Randall Munroe / xkcd.

Quick examples

- Shell:

date +%sprints the current Unix time in seconds. - Python:

import time; int(time.time())— seconds, ortime.time()for fractional seconds. - JavaScript:

Math.floor(Date.now() / 1000)— Date.now() returns milliseconds.

When you should use Unix time

- Machine-to-machine timestamps: compact, fast to compare, and well supported across platforms.

- Databases and indexes where you only need chronological ordering or durations.

- Protocols or binary formats that need a timezone-independent, compact numeric representation.

- Short-lived logging or metrics where space and parsing speed matter.

Practical rule: use Unix time for internal storage and calculations (sorting, rate limiting, TTLs), especially when you also store the timezone or a canonical representation elsewhere.

When you shouldn’t use Unix time

- For displaying dates to humans — it’s not readable and depends on timezone conversion.

- For legal/audit records where a human-readable, unambiguous timestamp (ISO 8601 / RFC 3339) is expected.

- When you need to express calendar concepts (local midnight, business days, recurring events) — those require civil/calendar-aware libraries.

- For measuring precise elapsed intervals in the presence of system clock changes — use a monotonic clock (e.g.,

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC)/time.monotonic()in Python).

Gotchas and tips

- Leap seconds: Unix time typically ignores them. If you need to account for leap seconds explicitly, Unix time may be the wrong primitive.

- Year 2038: 32-bit signed integers overflow for second-based Unix time. Use 64-bit integers for long-term storage.

- Precision: if you need sub-second precision, store fractional seconds (floats) or separate nanosecond fields.

- Always record timezone or store an ISO 8601 string when you also care about how that instant was presented to a user.

Recommended pattern

- For logs and APIs: prefer ISO 8601 / RFC 3339 formatted timestamps (e.g.,

2025-10-16T12:00:00Z) for human-readability and interoperability. - For internal calculations and compact storage: keep a Unix epoch in seconds or milliseconds (with a clear contract — seconds vs ms vs ns). Use 64-bit integers for durability.

- For durations or elapsed time: use monotonic clocks rather than wall-clock Unix time.

Conclusion

Unix time is a simple, practical tool — great for comparisons, storage efficiency, and interop — but it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. Pair it with human-readable timestamps and timezone information when you need clarity, and prefer monotonic clocks for measuring intervals.

Happy timestamping!